The 1974 federal election campaign began badly and only got worse.

As leader of the Progressive ConservativeĢżparty, Robert Stanfield was promoting price and income controls starting with a 90-day freeze to halt rampant inflation. Voters loved having a lid on prices but not on their salaries.

The policy was a tough sell and became even more troublesome as the media daily raised questions that required ever more complicated explanations.

As a result of her leadership, writes Rod McQueen, Bobbie Gaunt became the first Ford of Canada

Three weeks into the election, Stanfieldās campaign plane, filled with staff and press, left Halifax for a gruelling follow-the-sun schedule with numerous campaign stops along the way, ending in Vancouver 20 hours later.

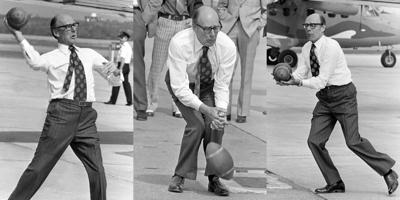

En route, we landed in North Bay to refuel. Everyone deplaned for a little fresh air. Someone began throwing a football around on the tarmac and soon Stanfield joined inĢżā tossing, running and catching the ball with an easy grace that belied his 60 years.

Canadian Press photographer Doug Ball shot a roll of film. As Stanfieldās press secretary, such was my delight with Stanfield looking so lithe and athleticĢżā just like that fellow Pierre Trudeau we were running againstĢżā that we held takeoff while I accompanied Ball into the airport terminal and helped him ship the film to pc28¹ŁĶųso his editors could put something on the newswires.

Imagine my chagrin the next morning when I saw the photo that appeared in just about every newspaper in the nation. You probably remember the one: Stanfield was stooped over, wearing a white shirt and tie, his empty hands clutched hopelessly together as the football tumbled to the ground below. He looked awkward and knock-kneed. His face was a grimace, his eyes clamped shut.

Newman the outsider embraced the country and got it right, but much of the country failed to

That photo became aĢżmetaphor for our beleaguered campaign. The pc28¹ŁĶųSun later asked The Canadian Press to send the complete 36-frame shoot, and published a series of photos showing Stanfield looking deft and agile, but the damage was already done.

Stanfield soldiered on to election day in July, but everyone knew that weād long since lost.

āZap! Youāre frozen!ā said Trudeau about Stanfieldās proposal for controls, but the following year adopted the very policy he had mocked in order to win his mandate. Politics and life arenāt fair, I know, but that volte-face seemed well beyond the pale.

When Stanfield died at 89 in 2003, the first recollections that came unsummoned to my mind were not the policy ideas, the more than 250,000 kilometresĢżI travelled, or the camaraderie of politics. It was Stanfieldās sense of humour. In his speech to a 1975 roast held in his honour, Stanfield said, āNo one has really laid a glove on me. It only proves, as Mackenzie King once said, you cannot roast a wet blanket.ā

Television interviews after Question Period in those days were conducted in Room 130S, in the basement of the centre block on Parliament Hill. On one occasion, Stanfield was standing in front of a row of cameras waiting patiently while a technician fixed a problem.

Veteran NDP MP Stanley Knowles entered the room, lingered at the back amid the silence, and finally said: āSpeak up, Bob, we canāt hear you.ā Replied Stanfield, āIām in the middle of one of my pauses.ā

Among the several thousand interviews Iāve conducted, two of the most riveting were with

Ah yes, Stanfieldās halting speech, a quality that ranked right up there with his solemn demeanour. Yet, year after year Stanfield gave by far the most humorous speech at the Parliamentary Press Gallery dinner, an off-the-record evening of drinking, skits and speeches. His deadpan timing was impeccable. Trudeau always delivered a dud.

A final story, as much about me, as the leader. Stanfield had borrowed a friendās house in Halifax for a vacation shortly before stepping down. Finlay MacDonald Jr., a local broadcaster, phoned me in Ottawa to see if he could interview Stanfield.

I knew Stanfield would be agreeable, so I called him and passed along Finlayās number. After I hung up, I realized Iād mistakenly given Stanfield the phone number of the house where he was staying. Oh well, I thought, heāll figure that out.

Finlay called the next day to say heād heard nothing. Fearing the worst, I phoned Stanfield.

Before I could explain, he said, āI havenāt been able to get through to Finlay. His lineās always busy.ā

āSir, Iām sorry, but I gave you your own number. Youāve been dialing yourself.ā

There was an exasperated sigh.

āYou guys are just sitting there up in Ottawa figuring out ways to ruin my vacation,ā he said. āI could have been prime minister years ago.ā

Yes, I wouldāve liked to have been on the winning side. So would he.

There was no final victory, but if youāre going to lose,Ģżfar better to do it alongside a gallant good man than win with connivers who will do anything and say anything in order to win at any cost to the country.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation