Most mornings, Rohin Bedi makes the same trek as thousands of others who live and work in the pc28¹ŁĶųregion: He catches a GO train from the suburbs into a city that has priced him and many other workers out.

But as a food delivery courier, Bediās commute is different: he has to lug the main tool of his trade ā his e-bike ā with him on public transit.

Unable to find regular employment, many newcomers, often young Indian men like him, have flocked to the gig economy, picking up jobs delivering food.

āYou just need a bike and an Uber account, and you can start making money,ā said Bedi, a 21-year-old from Punjab who lives in Mississauga.

Public transit struggles with food delivery bikes

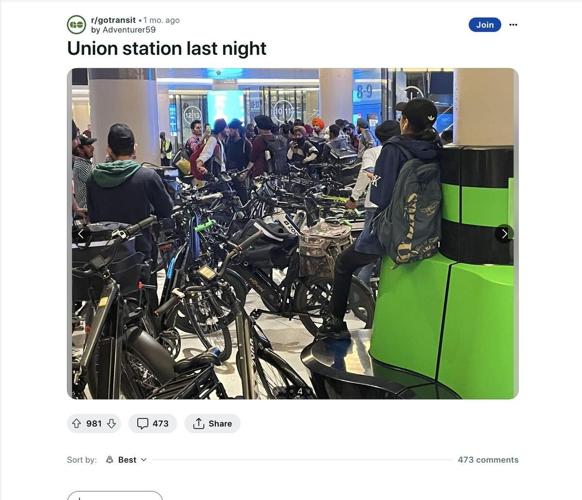

The bikes of food delivery workers piled together on an evening GO train heading into the suburbs.

The pc28¹ŁĶųStarBut in a job where density is king, making money requires making your way downtown. And with the growing number of food delivery couriers, finding room on public transit for their clunky two-wheelers has become a struggle, and .

On a recent evening, the Star watched a mad scramble among couriers at Union Station, who ā as soon as their trainās platform was announced minutes before departure ā quickly piled their bikes on elevators and dashed to secure a coveted spot.

Itās a scene repeated every day, but which seemed to come to a head last month, after BeyoncĆ© played Rogers Centre. Videos and photos from late that Saturday evening show the final trains back home due to increased demand and safety concerns. Some stayed at Union Station overnight.

(Metrolinx, the provincial agency that runs GO Transit, said it offered to store bikes overnight and shuttle couriers home by bus. āWe did not receive uptake on this offer,ā a spokesperson told the Star by email.)

Metrolinx adapts to delivery worker influx

The influx of bike-riding workers shuttling between the suburbs and Torontoās core has swelled so much in recent months that Metrolinx has had to adjust its operations in order to accommodate what one employee called the regional transit systemās new ābread and butter.ā

GO staffing and service changes have also thrown a spotlight on how private companies like food delivery apps rely on publicly funded infrastructure to fill the gaps in their low-cost business models.

Though exceptions are sometimes made, GO Transit officially allows only two bikes per car to ensure passengers can safely enter and exit the train. Many couriers now arrive to the station early with hopes of finding space, or else risk getting left behind.

In short, āthere are too many bikes,ā said Bedi.

In response to increased courier traffic, Metrolinx told the Star it had made several changes, including: adding occasional trains along the Kitchener line, a popular route for food delivery workers that connects Union Station to Brampton, Mississauga, Guelph and Kitchener; doubling bike capacity on select trains; and increasing staff on platforms to ensure bikes donāt exceed the coach limit.

Bedi, who delivers for more than one company, said he commutes earlier to avoid the rush of couriers who typically arrive downtown late in the morning and head back to the suburbs late at night.

When he first started delivering last September, he said it wasnāt as hard to find a spot for his bike. He attributes the recent increase in delivery workers to Canadaās decision to lift the 20-hour weekly work cap for international students last November, a policy which, unless extended, will expire at the end of 2023.

Metrolinx looks for help from food delivery apps

A throng of food delivery workers and their bikes at Union Station on Saturday, July 8, 2023.

RedditMetrolinx said it had also contacted companies like Uber Eats, DoorDash and Skip the Dishes āto inform them of the issue and of our policiesā with hopes to eventually āpartner with them on positive solutions that will address these challenges.ā

But Corey Mintz, author of āThe Next Supper,ā doubts the private sector will step in.

āThereās no law that says if you create more traffic you have to build more roads,ā said Mintz, whoās tracked the rise of food delivery apps.

According to him, so-called ādisruptive technologyā leaders like Uber and Airbnb ā purveyors of what he calls ā depend on infrastructure and resources they donāt have to finance, such as restaurants, cellphones, vehicles and public transit, as part of their business model.

In the case of the food delivery couriers, thatās resulted in the overcrowding of GO trains with bikes and the couriers who use them for work.

Mintz also pointed out that the apps also rely on āunderemployed people willing to work without the benefits, job security or safetyā traditionally associated with regular employment.

In separate statements, Uber Eats and DoorDash contested Mintzās assertion, saying that food delivery work appeals to those who enjoy independence and flexibility.

Though DoorDash said it was ācommitted to continue working with policymakers, transportation advocates, community leaders, and other stakeholders,ā neither it nor Uber Eats said whether it planned to partner with Metrolinx to solve the problem of the overcrowded trains. Skip the Dishes did not respond.

Low-income workersā migration a fixture in large cities

The daily migration of low-income workers from the suburbs to serve a more affluent clientele in the urban core is a fixture of most international cities, said Mintz, and itās unlikely to disappear in Toronto, where housing costs continue to soar.

But Metrolinx and delivery workers seem to be in agreement on how to fix the overcrowding: introduce dedicated bike coaches on the Kitchener line.

However, couriers will have to wait until the fall when Metrolinxās fleet of bike coaches ā currently used by sightseers along the Niagara corridor, whose busy season is soon ending ā will be redeployed to the Kitchener line. The transit agency said itās also working to procure more dedicated bike coaches, with e-bikes in mind.

Crowded train leads to missed income

For now, some couriers wait hours, watching several trains pass, before they can board, according to Vivek Dharmin, a 20-year-old Uber Eats courier and computer programming student. He said he once lost five hours of work because he couldnāt nab a spot.

Dharmin, who came to Canada in May from India, originally expected to work somewhere like McDonaldās, but food delivery became his only option because of a .

So far, heās ambivalent about his new home. āItās kind of good,ā a smiling Dharmin said after arriving at Union Station one recent morning. āNot as good as I expected.ā Someone had just stolen a bike he had recently bought for work. An exception among his peers who mostly ride e-bikes, Dharmin said he canāt afford to buy or rent one like Bedi.

Both hope they wonāt be in the delivery game for long.

Food couriers look for better jobs

Bedi wants to find a job in the trades, one that offers consistent pay and would help him qualify for permanent residency. With so many people eating out during summer, he said he often makes less than minimum wage: only $100 a day, minus the cost of transit (about $11 per day), and renting his e-bike ($200 per month).

Dharminās not so sure heāll stick around at all. āI think Iām going back to India,ā he said. āIām not going to stay here.ā There are too many people in his home country, he added, but you can easily find a job.

For now, he pays $400 a month to live in a shared Brampton apartment.

In Mississauga, Bedi splits a bedroom with a cousin in a shared apartment that houses five. He said his rent comes to $500 each month. Each is paying far less than the average asking rent for a room in a shared unit in Toronto, according to and Urbanation, a real estate data analysis firm.

As for living in Toronto, Dharmin is clear: āItās too expensive, man.ā

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation