Rob Butler sat in the dugout, watching the battle of a lifetime unfold in front of him.

The Blue Jays had charged out to a 5-1 lead against the Philadelphia Phillies, then squandered it two innings later and trailed 6-5. Butler looked on as Mitch Williams came in to pitch the bottom of the ninth, walking Rickey Henderson and giving up a single to Paul Molitor.

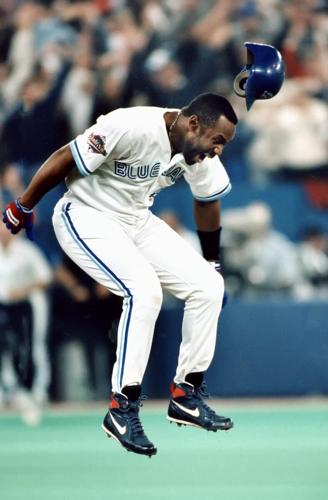

And Butler waited anxiously as Joe Carter swung wildly on a 2-and-1 pitch down and away, the precursor to one of the greatest moments in pc28¹ŁĶųsports history.

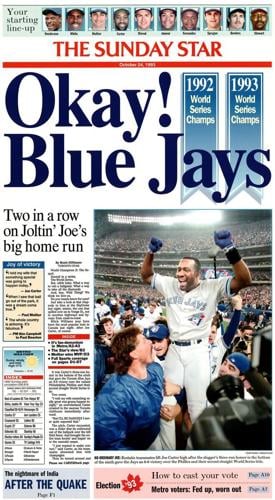

Monday marks the 30th anniversary of Game 6 of the 1993 World Series. A generation later, that game is still a linchpin of baseball fandom in Toronto.

That homer is all Jays fans want to talk to Carter about.

āTheyāll talk about where they were and what they were doing, because itās a moment where everyone realizes where they were and what they were doing at that time,ā Carter said in 2013.

For those in the dugout like Butler, in the broadcast booth like Jerry Howarth, or watching across Canada, the stories from that night need no prompting. Theyāre eager to share their brush with baseball history.

Butler remembers how it all unfolded: the crack of the bat, the teamās charge to home plate, the sensation coursing through his body as Carter rounded third and headed home.

āOh my God, holy F-word. It was unbelievable,ā Butler recalled thinking when Carter hit the three-run walkoff homer to win the World Series. āThat instant feeling of electricity going through your body ā¦ I have goosebumps now thinking about it.ā

Butler grew up at Main Street and Danforth Avenue in East York and was the only Canadian on the 1993 team. The outfielder played 17 games that year, returning from an injury for the post-season and appearing as a pinch-hitter in games 4 and 5 of the World Series.

He lived with his parents and took the subway to the SkyDome (as the Rogers Centre was then known) for Game 6. To even be on the roster was āincredible.ā

āIt was like winning $60 million in the (Lotto) 6/49,ā Butler told the Star in a recent interview. āThirty million Canadians all wished that they were me ā that they got to go down and sit on the bench and be in a Blue Jays uniform during the World Series. Iām pretty sure that I was the luckiest guy in Canada at that time.ā

While the Jays blew a four-run lead in the seventh inning and left the bases loaded in the bottom of the eighth of Game 6, Butler said nothing changed in the dugout. There was no self-doubt or worry of going to a Game 7.

āNo one ever said the word pressure,ā Butler said. āAny team was always in trouble until the last out against the Blue Jays that year.ā

Steps away from the dugout was Howarth, the longtime radio broadcaster for the Jays. He stood in the third-base camera well after going down to the field following the eighth inning to prepare for the post-game show.

Howarth watched as the door to the Phillies bullpen opened in right field and Williams stepped out. Howarth turned toward the Jays dugout.

āI see Rickey Henderson going from the far end ā¦ and heās giving everybody low high-fives all the way down to the camera bay,ā Howarth recalled.

Henderson, Torontoās leadoff hitter in the bottom of the ninth, told all of his teammates that Williams would walk him on four pitches. Minutes later, thatās exactly what happened, setting the stage for Carter.

Howarth had a front-row view of Carterās home run, stepping forward to get a glimpse of the ball soaring over the left-field wall. But he missed the moment millions of Canadians heard through their radios, on living-room couches and at dining-room tables across the country ā the words that have become the enduring memory of that home run.

āA swing and a belt, left field, way back, Blue Jays win it! The Blue Jays are World Series champions,ā play-by-play voice Tom Cheek exclaimed over the airwaves. āTouch āem all, Joe. Youāll never hit a bigger home run in your life.ā

On the field, those words were distant. After mobbing Carter at home, Butler jumped into the stands to celebrate with his family. He had grown up in government housing, clawing through the arduous path to make the majors. In that moment, he was a World Series champion.

āIt almost brings tears to my eyes because it was something that we all endured together,ā Butler said of his family. āIt was all really Canadian for us.ā

His family packed into the Jays clubhouse to celebrate. His mother made the most of it, stuffing champagne bottles into her pockets and somehow getting her hands on one of Carterās bats.

āThat whole feeling of being together with my family and the team,ā Butler recalled. āWho gets to do that? I got so lucky and I donāt even know why.ā

Later that night, Howarth asked Cheek about his iconic call.

āHe said, āWhen I started to look at the home-run ball and I knew it was gonna clear the wall, I started to look at Joe going down the first-base line jumping up and down,āā Howarth remembered Cheek saying.

āāI said, āTouch āem all, Joe,ā because I didnāt want him to miss first base.āā

The call is considered one of the greatest in baseball history. Cheek died 12 years later in 2005 from a brain tumour.

āThat was a perfect moment for Tom to have seen what had happened, and then make the exact, precise call to honour what was happening,ā Howarth said.

Butler stayed at the SkyDome until the early hours of the morning, arriving back home in East York at 3 a.m. Thatās when his friends started showing up. His mother, who had received a dozen World Series baseballs signed by the entire team, started handing them to his friends.

āMy mom, I guess, thought it was Christmas,ā Butler said. āI ended up with one World Series ball. All my friends somewhere around East York have the rest.ā

Wherever those balls are stashed 30 years later, the memories of the 1993 World Series still flow.

āNobody was better than the pc28¹ŁĶųBlue Jays in 1993. No team in the world was,ā Butler said. āHow there hasnāt been a movie made about it is beyond me.ā

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation