Ontario is facing its worst measles outbreak in 30 years, with nearly four times the number of cases reported in the past decade.

According to the most recent measles surveillance , released Thursday (and later updated on Friday by PHO to correct data errors) and tracking data up to March 12, 350 cases have been reported across 11 public health units since October. This includes 31 hospitalizations, nearly all involving unvaccinated individuals, mostly children.

Until last year, measles was rare in Ontario, with only 101 cases reported between 2013 and 2023.

However, after increased global measles activity in 2024, more cases have been reported in Canada, with 64 cases reported in Ontario last year alone.

Here is what you need to know about measles and how to keep your family safe.

What is measles?

Measles is a highly contagious respiratory infection spread by airborne particles from coughing, sneezing or touching your eyes, nose or mouth after touching an infected surface.

Symptoms include fever, runny nose, red watery eyes, cough and a red, blotchy rash. Symptoms typically appear seven to 21 days after infection, and people can spread the disease up to four days before and after a rash appears.

Most people recover in two to three weeks, but complications such as ear infections, pneumonia and diarrhea can occur, often requiring hospitalization.

Severe complications include respiratory failure, brain inflammation, and even death.

Where are the outbreaks happening?

The first measles case was reported on Oct. 28, 2024, in New Brunswick, after exposure from travelling.

Since October, 258 confirmed and 92 probable cases of measles have been reported in Ontario, with 73 per cent of these cases in children or adolescents.

All 11 public health units reporting measles cases are in the southern regions of the province, except for North Bay Parry Sound District Health Unit. of all measles exposures by health unit.

Dr. Allison McGeer, an infectious diseases specialist at the University of Toronto, explained that this outbreak could be occurring for a couple of reasons. One is the “catching up” of virus rates, such as measles, influenza, and RSV, following reduced transmission during the pandemic. Another is increased travel, particularly from countries where measles is more common.

This outbreak is primarily affecting unvaccinated communities with “religious and cultural reasons not to be vaccinated,” according to McGeer. “This is not the general population of Ontario being unimmunized against measles,” she said.

Is measles preventable?

Short answer — yes.

According to experts, immunization remains the best protection against measles.

Children over one year old and most adults born in or after 1970 require two doses of a measles-containing vaccine. Those born before 1970 are considered immune due to higher likelihood of exposure to the disease prior to the vaccine’s introduction.

In a statement, Dr. Kieran Moore, Ontario’s chief medical officer of health, said 96 per cent of measles cases in the province are happening in individuals who are unvaccinated, or whose vaccination status is unknown.

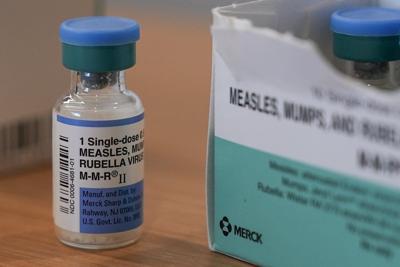

“The measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine has been in use for more than 50 years and is proven to be one of the safest and most effective vaccines available,” Moore said in his statement.

“Children who are fully immunized with two doses of the measles vaccine are nearly 100 per cent protected, with one dose estimated to be up to 95 per cent protective.”

McGeer said receiving the vaccine is “not an absolute guarantee you won’t get measles,” but “if you do get measles, it will not be severe.”

What to do if you’re sick or at risk?

Dr. Allan Grill, lead physician at Markham Family Health Team, recommends checking your vaccination records if you were born in or after 1970 to make sure you have received two doses, as two doses weren’t required in Ontario until 1996.

Adults who did not receive their second dose should contact their primary care provider, visit a walk-in clinic, or call their local public health unit, as many are doing vaccination clinics.

Those who are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated should get vaccinated at least two weeks before travelling, Grill advises. Infants between six and 11 months who are not eligible for the measles vaccine yet can receive an additional vaccine before one year. Grill also suggests that children who’ve only received one dose should consult their doctor to get their second dose sooner.

For those who are unable to get the vaccine, such as pregnant women or those who are immunocompromised, Grill said there are still alternatives.

“If they present (symptoms) within six days of exposure, we can actually get them something called immunoglobulin, which is when we give them actually antibodies against the measles virus,” he said.

If you or a family member begin showing measles symptoms or suspect you may have come into contact with measles, Grill said to call ahead to your doctor so they take precautions to prevent the spread of the disease, and to stay home from work or school if you are feeling ill.

Correction - March 25, 2025

This article was updated from a previous version to reflect updated numbers. The PHO Measles Report used for this article, originally released on Thursday, March 13th, contained data errors and was replaced with a corrected report by the PHO on Friday, March 14th, featuring the corrected case counts. The corrected data from March 14 shows a total of 350 measles cases, not 372. There have been 258 confirmed and 92 probable cases, not 277 and 95 respectively.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation