A 53-year-old Soviet spacecraft built to survive the hellish conditions of Venus ‚ÄĒ where the sky glows yellow, the temperature soars to 460 degrees Celsius and the atmospheric pressure is akin to being crushed a kilometre below the ocean‚Äôs surface ‚ÄĒ is about to hit Earth.

No one knows where. The experts aren’t quite sure on when, either. And even worse: Designed for success in one of our solar system’s most deadly environments, it might even reach the ground in one piece.

The good news is the probe, officially the Cosmos-482 Descent Craft, is incredibly unlikely to hurt anyone when it comes crashing down at 25,000 kilometres per hour sometime late Friday evening or early Saturday morning.

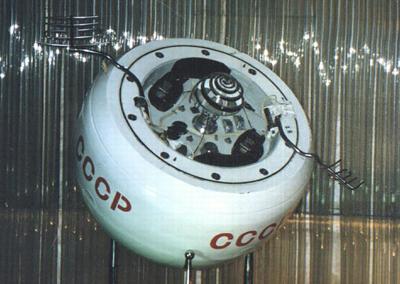

The 500-kilogram, one-metre-diameter probe has been orbiting Earth ever since its failed launch by the Soviet Union in March 1972. The Russians launched two identical spacecraft that month, and one ‚ÄĒ Venera 8 ‚ÄĒ successfully made it to Venus, surviving on its surface for 63 minutes and confirming the brutal conditions on the planet.

Its twin launched four days later. While the Soviets successfully parked it in orbit around Earth, their plan to then launch it to Venus failed. Instead, it broke into four pieces ‚ÄĒ two of which re-entered Earth‚Äôs atmosphere within 48 hours, and two of which were sent into orbit for decades.

Until this week. Thanks to years of atmospheric drag slowly pulling it back to Earth, one of the pieces, thought to be the lander probe, is about to come back down, with a small portion of its potential landing area in Canada, including spots not too far from Toronto.

Update: ‚Äôs latest autonomous predictions show that the re-entry window of object Cosmos-482 Descent Craft is 2025-05-10 06:07 UTC ¬Ī290 min. We keep observing the object & performing analyses; stay tuned for more updates. Read more

‚ÄĒ EU SST (@EU_SST)

But this spacecraft is unique. Unlike the thousands of Starlink satellites populating low Earth orbit that are designed to deorbit naturally after five years and burn up in the atmosphere, Cosmos-482 was designed for some of the most brutal conditions in the solar system.

‚ÄúVenus is a hell hole,‚ÄĚ said Samantha Lawler, an astronomy professor at the University of Regina who researches space debris. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs hotter than a pizza oven ‚Ķ If you could walk on the surface, it would almost be like swimming, because the atmosphere is so dense.‚ÄĚ

NASA has only landed successfully on Venus once. The Russians, far more keen on exploring the planet, made more than 15 attempts, many of which failed. Their biggest success came in 1982. That year’s probe lasted on the surface for all of 127 minutes.

‚ÄúThey‚Äôre like tanks,‚ÄĚ Lawler said. ‚ÄúThese probes are built to withstand hell and now one is gonna come through Earth‚Äôs atmosphere ‚ÄĒ which seems relatively gentle, even at 25,000 kilometres an hour.‚ÄĚ

So instead of getting ripped up in a fireball far above our heads, Cosmos-482 may remain intact when it comes for us.

‚ÄúThe Cosmos-482 Descent Craft is a remarkable object deserving careful monitoring,‚ÄĚ the EU Space Surveillance and Tracking (EU SST) said on its website. ‚Äú(It has) a titanium shell designed to withstand the extreme accelerations, heat and pressure of a Venus re-entry.‚ÄĚ

It will be, Lawler predicts, like a meteorite impact. If the probe hits land, it might leave a small crater in its place. If it hits a city, that would be ‚Äúreally, really bad,‚ÄĚ Lawler said.

Even so, experts are struggling to predict exactly when and where Cosmos-482 will come down. As the predicted re-entry gets nearer, predictions from the and , a satellite tracking station in the Netherlands, have grown more specific, but there is still a re-entry window several hours long and multiple orbits wide.

It‚Äôs so hard to predict, Lawler explained, because the density of Earth‚Äôs atmosphere is constantly changing. There‚Äôs fluctuations in weather on the ground, but also with space weather ‚ÄĒ the charged, fast-moving particle bursts sent out by the sun that cause the northern lights.

In fact, when a strong geomagnetic storm hit Earth last May and painted the aurora borealis across the skies in parts of Toronto, satellites in low Earth orbit lost altitude and had to be corrected. A similar guessing game is happening with Cosmos-482.

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs travelling at 25,000 kilometres per hour,‚ÄĚ Lawler said. ‚ÄúEven a few seconds‚Äô difference is a huge distance on the ground.‚ÄĚ

Still, the odds the probe ‚ÄĒ only a metre wide ‚ÄĒ does any damage are incredibly low. Seventy-one per cent of Earth is water; only a fraction of all land is inhabited.

And compared to other re-entering spacecraft over the years, it could be worse.

‚ÄúThis one doesn‚Äôt have a nuclear reactor,‚ÄĚ Lawler said, ‚Äúso that‚Äôs great.‚ÄĚ